Shouting with one voice

Maybe it's just a combination of circumstances, or maybe the cup is full, but the fact remains that a number of musicians in French-speaking Switzerland raised their voices last May to express their concern and growing difficulties in practicing their profession.

In early May, the cellist Sara Oswald published an open letter on social networks, in which many artists recognized themselves. In it, she writes: "I'm exhausted from always earning a pittance, while the cost of living is rising. The exhaustion of always having to fight to qualify for the health insurance subsidy, without which I'm clearly closing up store. The exhaustion of having to do tons of paperwork to get my projects off the ground."

She reminds us that professional training does not protect musicians: "I'm a product of the HEMU Lausanne, and I did a Master's at the HEM Geneva in baroque cello. I've been a professional for 23 years now. There are months when I earn just CHF 400, thanks to a single concert in 30 days. Yes, I could teach, I could play in an orchestra. But it just doesn't suit me. I love writing music, composing for projects and doing concerts. I learned this profession for that. You need time to create, to work on your instrument, to do booking and administration (more than half my time). After a day's teaching, who still has the energy to sit down in their room and find the inspiration for a new, original composition idea? Because, yes, as well as being a musician, you have to learn how to sell yourself. For my part, I could say that my work takes up more than 100 % of my time. In short, it's all I do. Work. And for free."

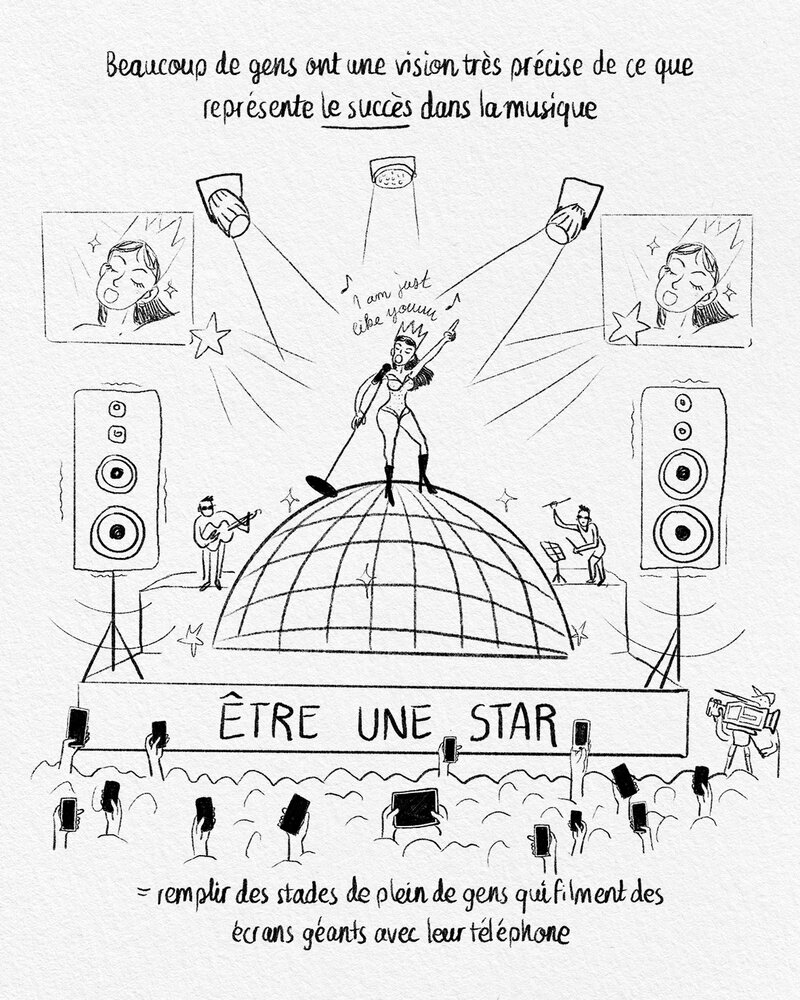

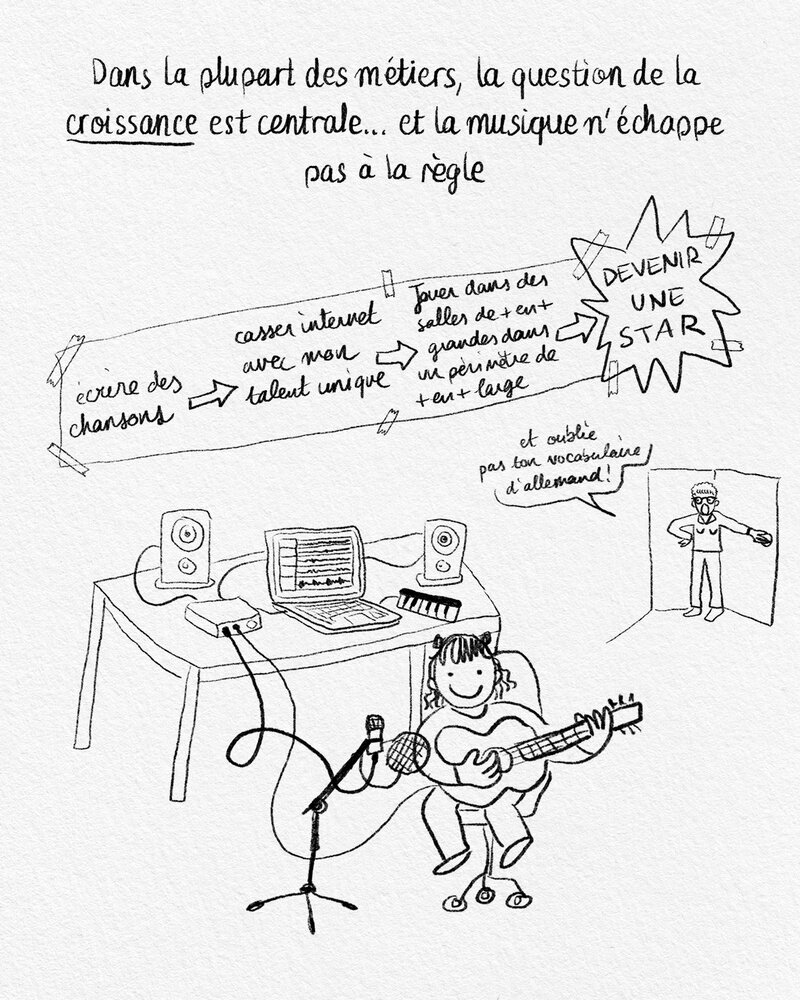

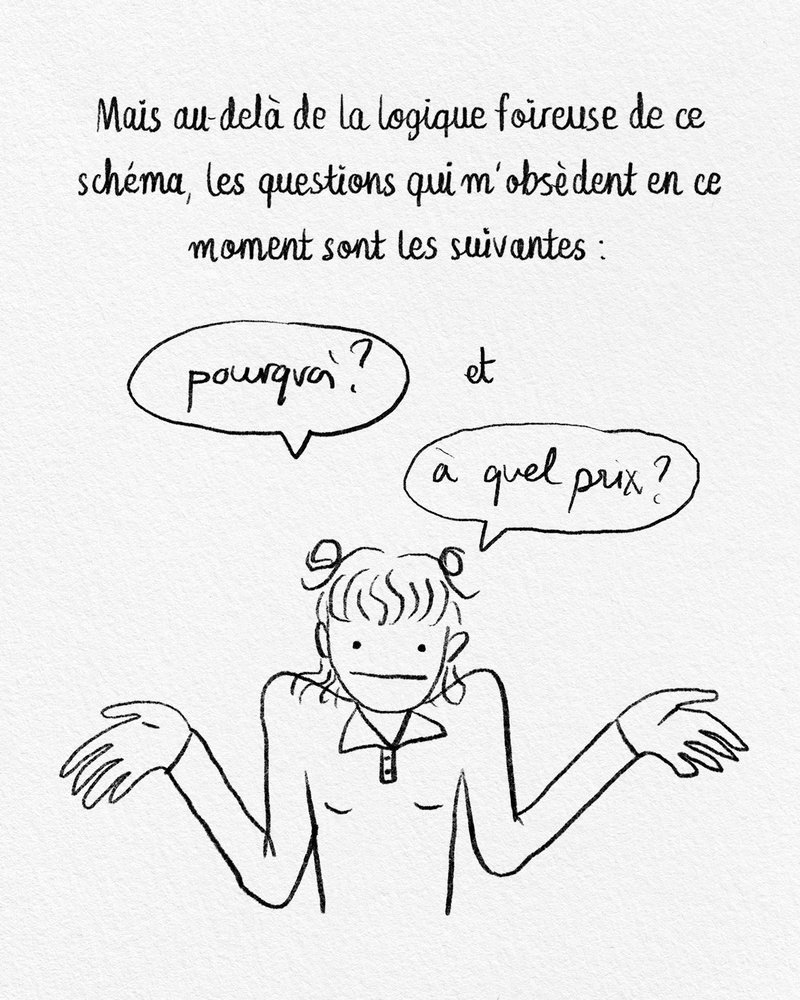

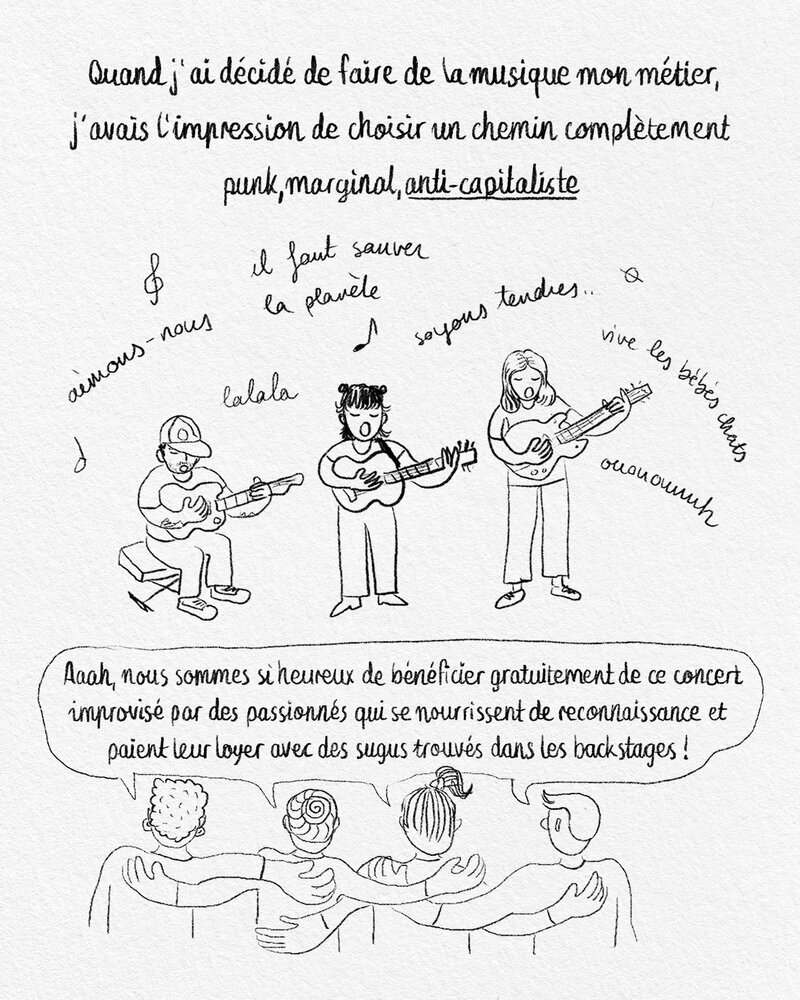

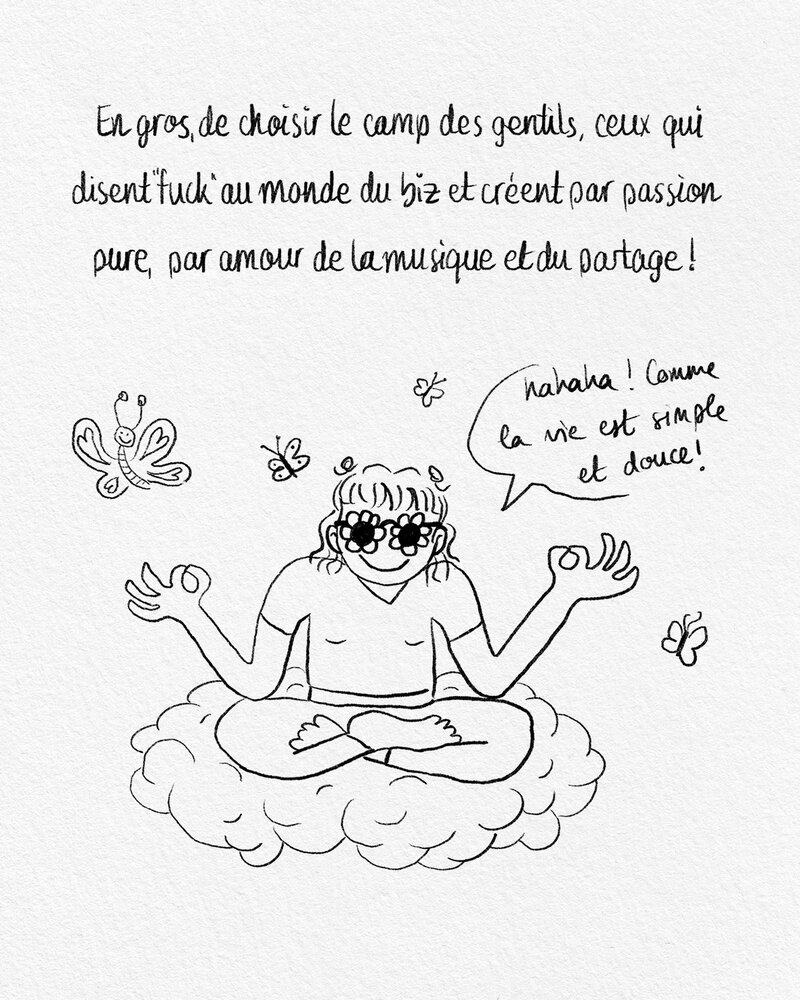

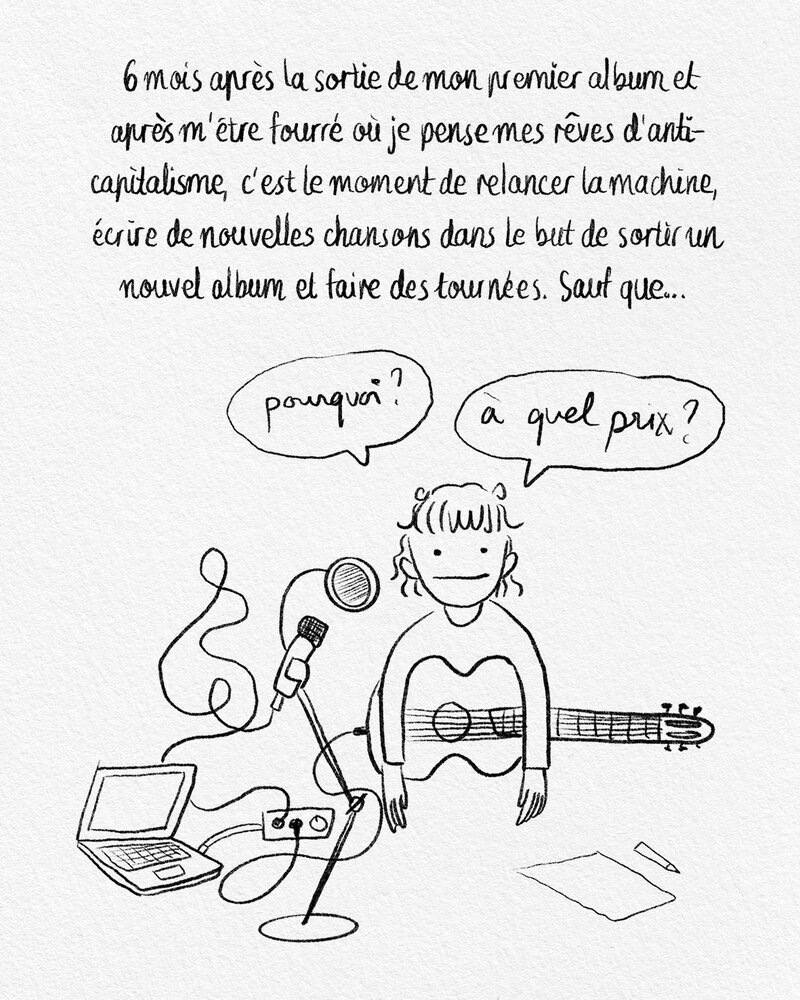

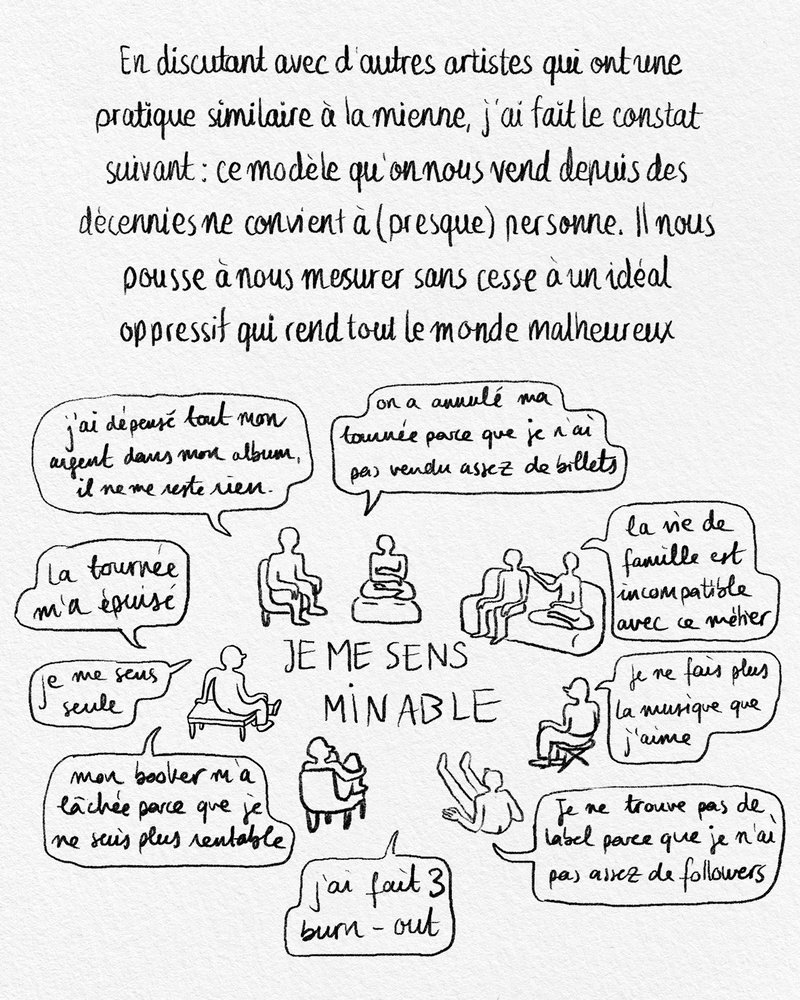

For her part, Valais singer Meimuna expressed his unease in drawings, a series of 14 plates, also visible on social networks, which reflect the same concerns and address an existential question: "should we leave the music business?"

Paleo, the stockings

On May 2, the subject was broached on RTS by a third artist, Moictani, a singer on the bill at this summer's Paléo Festival. We learn that she, too, has to make do with fees of 200 to 300 francs per concert, and that Switzerland's biggest festival is no more generous: the entire budget is used to pay the headliners' lavish fees. We dream of a Paléo that invites two fewer to pay lesser-known artists, even if it means selling out its 200,000 tickets in 30 minutes instead of 13.

Generally speaking, we dream of a society that is aware of the indispensable role played by culture, and of the need to defend our own culture, not just a few stars from across the Atlantic. This requires the support of state structures that are not called into question every time money is needed to save a bank in bankruptcy here or compensate for customs taxes there.

Tariff recommendations recently drawn up by Sonart are a very good step in this direction. Following the numerous reactions to her open letter, Sara Oswald has launched an online survey with the aim of drafting a musician's manifesto, which will almost certainly be published in Sonart. Le Temps. Because to move forward, Swiss musicians are unanimous in saying that they need to join forces, and speak - or rather shout - with one voice. La Swiss Music Review is also here to do just that.

Open letter from Sara Oswald: Invisibles

"It all started a few years ago. A beginning of fatigue. An incipient annoyance, at still having to explain that I want to be paid to record on this or that person's record or to go and do a concert. A growing sense of disbelief at how far removed one's belief in the life of an artist really is. I always hear the same old line: "It's wonderful to make a living from your passion".

As the years went by, I began to feel exhausted, having to travel thousands of kilometers to play in the depths of France for a fee of 300 Euros, not including travel costs. I question the point of playing elsewhere, and the desire for exoticism always takes over, well beyond the realms of reality. The exhaustion of always earning a pittance, while the cost of living rises. The exhaustion of always fighting to qualify for the health insurance subsidy, without which I clearly close up store. The exhaustion of doing tons of paperwork to get my projects off the ground.

And speaking of projects, lately, at the age of 47, I've been feeling an undisguised anger, born of the refusal of a subsidy that jeopardizes a very personal show, the fruit of my labor over the past 4 years, because "we can only subsidize a third of the projects for which we receive applications". I can well imagine that the budget for culture is not infinite. Talking to a lot of friends who are independent musicians like me, I learn that some put all their meagre savings on the table to pay the costs of producing and making a record (it goes without saying that we don't get a kopek from Spotify and friends), others squander a small inheritance to "keep making projects", still others throw in the towel in disgust, while others burn out. We suffer. More and more. Silently. Invisible.

I'm a product of the HEMU Lausanne, and I did a Master's at the HEMU Geneva in baroque cello. I've been a professional for 23 years now (Bachelor's degree in cello in hand). There are months when I earn just CHF 400, thanks to a single concert in 30 days. Yes, I could teach, I could play in an orchestra. But it just doesn't suit me. I love writing music, composing for projects and doing concerts. I learned this profession for that. You need time to create, to work on your instrument, to do booking and administration (more than half my time). After a day's teaching, who still has the energy to sit down in their room and find the inspiration for a new, original composition idea? Because, yes, as well as being a musician, you have to learn how to sell yourself. For my part, I could say that my work takes up more than 100 % of my time. In short, it's all I do. Work. And for free. Needless to say, rehearsals aren't paid either. Neither is instrument work, composition, time spent putting together a concert program, hours in front of the computer making budgets or presentation files. Only the concert itself is paid for. And commuting is often a struggle. As Stéphanie Arboit points out in the excellent study by Marc Audétat and Marc Perrenoud published in Le Temps on April 25, the average fee for jazz and contemporary music is CHF 300. Even if you play every weekend, which I don't think happens to any artist in Switzerland, it's extremely complicated to make a living from it.... I'm thinking of Meimuna's beautiful drawings (see Instagram April 25), which speak so well of all this.

Isn't it sad and shocking to think that you learn a trade, professionally, by going to college, learning on your own or doing other training, and then you spend your life making music and can't make a living from it? What's also complicated, in my opinion, is the unfair competition in the profession. Given that we're already in such a precarious position, I think that agreeing to go out and play for less than CHF 300 does our profession a disservice, making it seem as if our performances have no value. Hence the question: what is a professional musician? someone who makes a living from his or her art? someone who has studied in a school? someone who has no other income than music?

Over the last few days, I've spoken to a lot of musicians, and everywhere I feel this exhaustion, this healthy anger, this despondency, and I tell myself that something has to be done.

What solutions are we hearing about? How can we become visible? What can we do to make ourselves heard, to unite? And above all, what do we propose to change things?

This morning, I feel tired of my/our invisibility."

Meimuna's drawings: Should we leave the music business?

Drawings: Meimuna