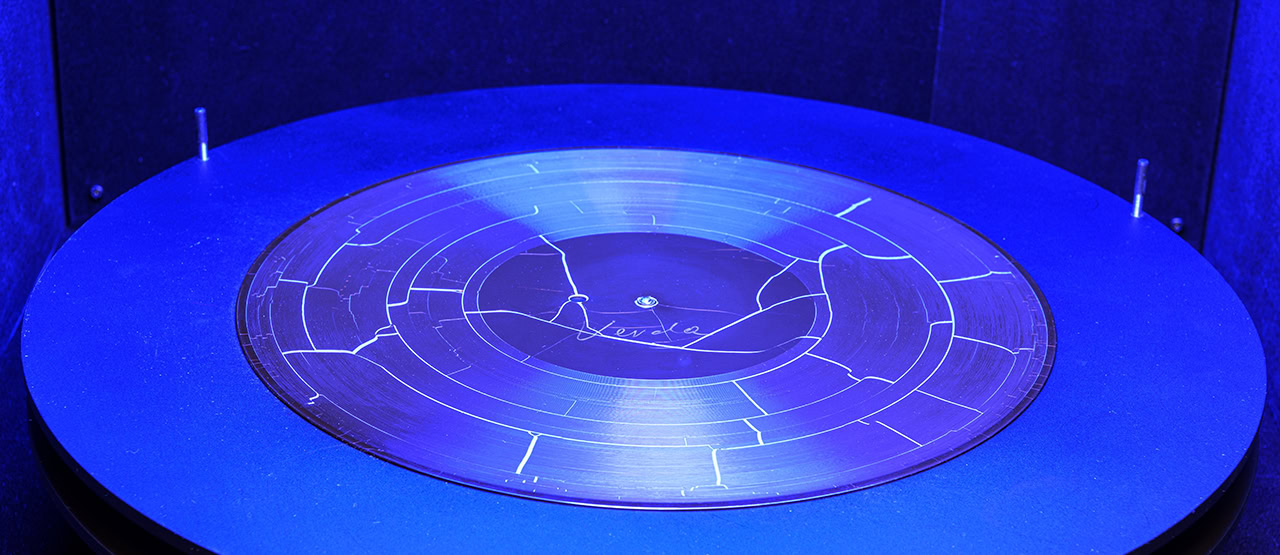

Farnaz Modarresifar - contemporary santur sounds

Santour virtuoso and Franco-Iranian composer Farnaz Modarresifar offers a resonant universe and develops an original contemporary language for her instrument, while demonstrating her attachment to tradition. Interview.

Photo: Farid Modarresifar

In Geneva, the Archipel festival devoted a portrait concert to Farnaz Modarresifar during its 2025 edition.

Farnaz Modaressifar, what makes this Persian table zither called santour so special?

I can say that it is above all the resonance of this instrument that makes it special, as it has no damper, unlike the Chinese zither, for example. I often say that the art of interpreting the santur is the art of interpreting resonance. As far as I'm concerned, I work a lot on the harmonic and resonant layers that best characterize this instrument. The classical santour I play has 18 bridges, 72 strings and a soundboard. The soundboard is traditionally made of walnut, which I particularly like for its sound, but it can also be found in other woods. The strings are struck with two light sticks, which characterizes the specific playing style of this instrument. The santour, like most Persian classical instruments, is not powerful, and in my opinion, all its richness unfolds in this intimate aspect. That's why some of my music requires very careful listening.

You create works that are firmly rooted in the 21st century.e You compose for all types of ensemble, from solo instrument or voice to chamber orchestra. Pianist Maroussia Gentet of Collectif G describes your works as "exploring the tragic aspect of resonance"...

We have several collaborations with Maroussia Gentet as pianist and member of the collectif G, a group of musicians whose work and stage presence I greatly admire. It's interesting that she picked up on this "tragic" aspect of my work as a performer, but also as a composer. I think that the personal and social histories I've lived through in Iran and France, this cultural duality that defines me, as well as the literary thought that is fundamental to Persian music, somehow form the poetic and dramatic outlook I've acquired as a creator. Through the classical Persian musical culture in which I was immersed from the age of 6, and the academic path I followed in Teheran, I am permanently linked to and touched by Persian literature and poetry. This dramatic and sometimes tragic aspect is therefore always present, and inspires me in my work. It's like a personal passion.

You are sensitive to the world of sound, but also to the world of literature. Since you were a teenager, you've been particularly interested in ancient Persian mythology and the dream analysis proposed by Freud and Jung. You yourself write poems based on your dreams...

Yes, from the age of 19-20, I became very interested in the psychoanalytical studies of Freud and Jung, as well as in the transcriptions and interpretation of dreams. I've always been fascinated by delving into the unconscious of others. It has to be said that in Iran, it was not always easy to find translations of Freud's talks. But my mastery of English and French gave me access to several sources in these fields, and enabled me to complete my reading. At the same time, I was also reading a great deal about ancient Persian mythology. All these books, including Indo-American stories and myths, have stayed with me to this day. Then I started writing what I call a kind of "red book", collected in two volumes and based on transcriptions of my dreams. A small collection in Persian has been published in Iran, and a French translation is planned...

To what extent do these readings inspire your music?

Whether novels, poetry or other literary genres, they have a direct influence on my work as a musician. The realm of poetry is, in my opinion, the purest state of a writer's unconsciousness. I usually write the lyrics for my music when I'm composing it myself. So I base myself on the soundscape of the texts, which I imagine most of the time from my dreams...

Singing is one of the pillars of traditional Persian music. It is also present in some of your compositions...

Absolutely. In fact, one of the fundamental rules of Persian classical music, also known as art music, which I've been practicing since I was a child, is that it is closely linked to Persian classical poetry and literature, conveyed by the singer. Singing and the voice therefore play an essential role in this music, which is based on the mood of the chosen poems. In some of my pieces, I try to unite the voice and the instrument as a single body... My music is based as much on the study of the timbres of contemporary Western music as on the melodic and modal contours of traditional Persian music, without, for example, composing tasnifs on Persian modes, which is a well-known practice among performers of traditional music. I sometimes borrow a few lines from great classical poets such as Hafez and Ferdowsi, or great figures of contemporary poetry like Forough Farrokhzad, quoting them in the score, without them being recited or sung. This allows the performer to grasp the direction in which the music is heading...

After studying at the National Conservatory of Music and the University of Teheran, you pursued in-depth training in composition at the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris- Alfred Cortot and the Conservatoire de Boulogne Billancourt, followed by training in improvisation and musical creation at the University of Paris VIII. How did your career path lead you to the world of composition?

A decisive trigger occurred in 2009: during an academic trip to Germany, I had the opportunity to hear for the first time at the Cologne Philharmonic a performance ofAtmospheres by György Ligeti. It was a real discovery for me! This first contact with contemporary music really aroused my curiosity. So much so that when I returned to Iran, I started taking composition classes, without really intending to become a composer. For about two years, my participation in my teacher Kiavash Saheb Nassagh's exploratory ensemble enabled me to explore contemporary music with the santur. It was then that I began to catalogue and work on modes of augmented or contemporary playing, on the question of timbre and on the sonic blending of this instrument within an ensemble or orchestra. After graduating from the University of Teheran, I was carried away by a passion and decided to perfect my composition skills in France, a country I chose above all for its musical aesthetics. But the history of a strong cultural relationship between France and Iran also played a role in this choice. Improvisation in the contemporary style has always fascinated me deeply, which is why I also pursued a master's degree in improvisation there.

For the Archipel Festival, you have proposed a selection of works inspired by your poems and texts. It's a program that allows you to trace the contours of your research. There are written pieces that you perform with Ensemble Recherche, as well as solo and collective improvisations. How did you come up with the dramaturgy for this program?

Initially, the program was the result of purely material constraints, particularly with regard to instrumentation, since the piano is present in almost all my pieces, but the festival had no piano available for this concert. With the musicians of Ensemble Recherche, we therefore rethought the dramaturgy and the choice of works, taking into account the limited orchestral resources available for the festival. The program includes pieces written over the last ten years, such as : The sun only the sun for solo violin (2018), Gabbéh for viola and santoor (2019), The pearl fisherwoman - flute and clarinet (2015), Che si può fare - voix et santour (2015)... It also includes improvisations inspired by Dream Stroll (2022), a piece I originally created for the Orchestre de Radio France. It's a suite of miniatures based on my dreams and poetry. Other improvisations are based on texts by the great Persian mystic poet Farid al-Din Attar. The dramaturgy is thus conceived as a musical and poetic trajectory. The concert begins with a solo santur improvisation based on the classical Persian repertoire (the radif), allowing the audience to discover the sound identity of this traditional instrument. From the very first rehearsal, the Ensemble's musicians were able to enter fully into the universe and spirit of each piece, even during the improvisation parts. It was a wonderful experience for us all!

How did your collaboration with Ensemble Recherche, recognized as one of the leading players in new music, come about, and how does it feed into your personal projects?

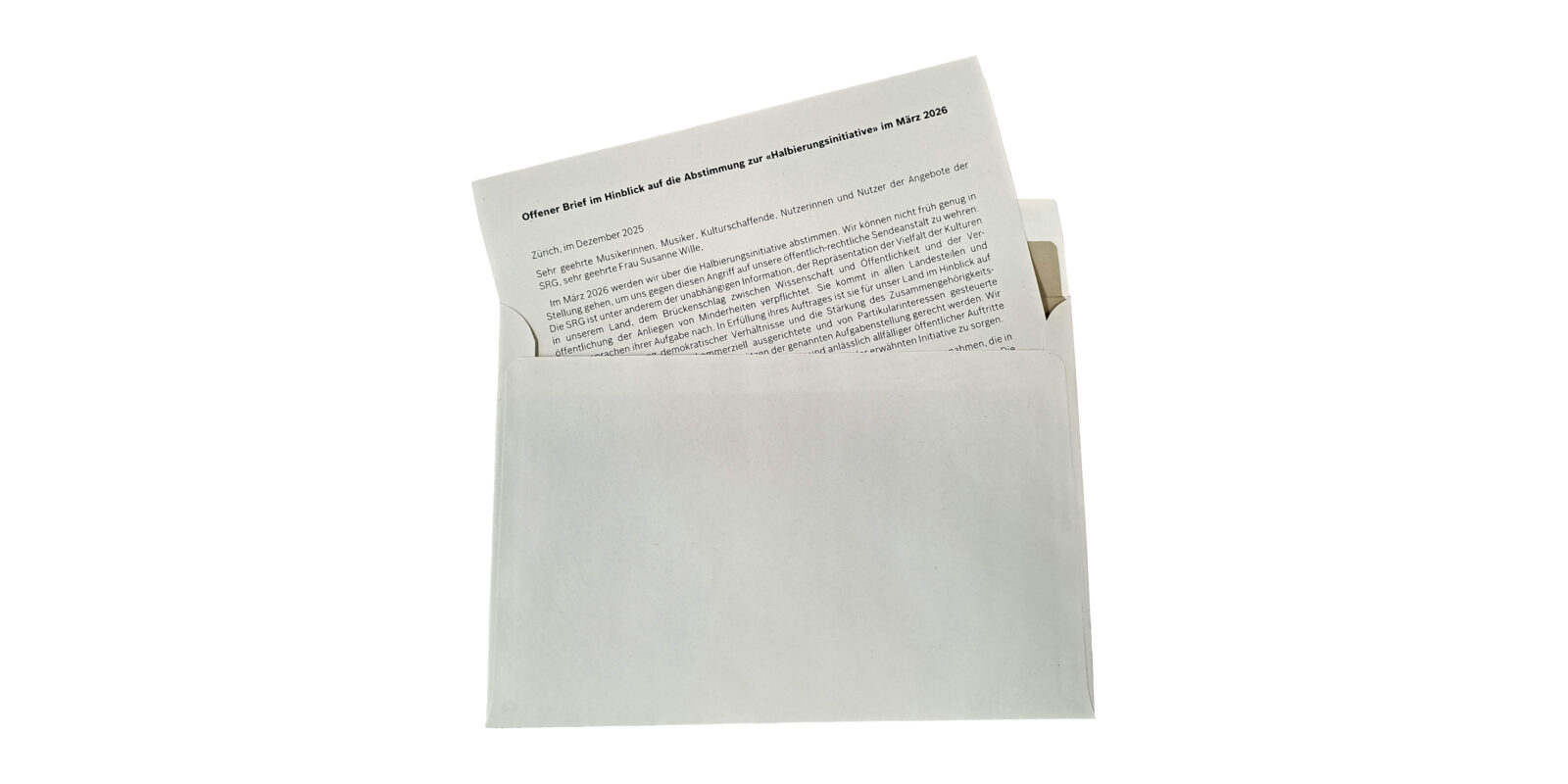

It was in 2023 that Paul Clift, then Artistic Director of Ensemble Recherche, contacted me with a view to working with the group. The proposal obviously filled me with joy! Our collaboration took some time to materialize, for logistical and financial reasons. But it was in 2025 that we were fortunate enough to be able to launch this project together, as winners of theImpuls Neue Musika Franco-German-Swiss fund for contemporary music. We imagined two distinct concerts, with different instrumentations. First, as part of the Archipel Festival in Geneva, with the participation of Marie Soubestre on voice, and a selection of musicians from Ensemble Recherche. Then, a premiere for the full ensemble and voice is scheduled for December in Fribourg. Working with this ensemble, as well as with the Orchestre de chambre de Paris, Ensemble Ars Nova and ProQuartet-CEMC, gives me a new perspective and a richness of interpretation, and provides enormous nourishment for my creativity, my explorations of the chamber repertoire, and my desire to further develop the contemporary santoor repertoire.